Recently

I went looking for the TV movie Shackleton starring Kenneth Branagh

in the lead role. I had not seen this film since its first release on

Australian TV in 2003. It made a huge impression upon me. This film was bound

to captivate audiences around the world because of the immensity of the ordeal

suffered by the entire crew, including Shackleton himself as leader of the

expedition, and also Frank Hurley who was the official photographer on this

ill-fated adventure. The images which Hurley recorded from the first part of

this expedition up until the men reached Elephant Island in April 1916 have

remained powerful icons of polar exploration and failed expeditions since they

were released to the public in 1919, although newspaper accounts of the entire

event including the rescue had been available after August 1916.

Movie

footage from this expedition was used to create films for release under two

main titles: “South” and “In the Grip of the Polar Ice”.

In his

NFSA essay ‘AKA. Home of the Blizzard’, Quentin Turnour wrote:

Hurley shot footage to complete the film, but the work doesn’t see release until 1919. “IN THE GRIP OF THE POLAR ICE” is the title of the Australian lecture film; the UK release is called “SOUTH”.

As I

could not locate a copy of the “SHACKLETON” movie I watched the two hour Nova

documentary called “ENDURANCE” (click link) instead. I had not seen this doco

previously, but I found it totally gripping. I won’t bother to list its few

shortcomings. I was overwhelmed about this account of the expedition in so many

ways! The ship was well named “Endurance” despite the irony of the fact it

failed to endure the onslaught of the ice. Because the ship was so named, the

name “Endurance” now stands for Shackleton’s entire mission from the beginning

to end. It stands for the mighty effort of all the crew and team members, their

heroic performance under the most trying, debilitating circumstances; the fact that they survived as

a team despite their different personalities and temperaments; and most of all,

the astonishing qualities of leadership Shackleton provided throughout the

whole crisis. Finally, Shackleton got every member of his expedition home

alive, against all the odds which were stacked so heavily against them.

I now

return to the central throughline of my essay, “The Search for the Truth in

Documentaries”. Here we encounter a singular conundrum… the veracity of the original

films which were released about the Shackleton expedition compared with

the truthfulness of any films which derive from those early films,

including a documentary such as Nova’s, or a dramatised TV serial account such

as “Shackleton”,

featuring Kenneth Branagh and directed by Charles Sturridge.

Let’s

go back to the rare film and photographic footage of the period 1914 - 1919.

I begin

in 1914 because that is when Frank Hurley joined Shackleton’s expedition,

and I will end with 1919 because that is when these early versions of the

filmed footage were released as films. Near the end of that period Hurley was

engaged as a photographer in action in WW1, from 1917 to March 1918.

From Wiki:

In 1917, Hurley joined the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) as an honorary captain and photographed many stunning battlefield scenes during the Third Battle of Ypres. In keeping with his adventurous spirit, he took considerable risks to photograph his subjects, also producing many rare panoramic and colour photographs of the conflict. Hurley kept a diary in 1917-1918 chronicling his time as a war photographer.[7] In it he describes his commitment "to illustrate to the public the things our fellows do and how war is conducted", as well as his short-lived resignation in October 1917 when he was ordered not to produce composite images.[8] His period with the AIF ended in March 1918.

I will return to many of the points raised in this summary from Wikipedia later in the essay, especially the issue of “composite images” which caused so much criticism of Hurley.

On YouTube I found an interesting video compilation (click link), a “tribute” to Shackleton and his expedition. This is how it was described by its creator Pete Vassilakos:

This

tribute piece is created from some of the movie footage and some of the stills

shot by Frank Hurley. Running only 21 min 36 secs it is accompanied by a

soundtrack of music and sound effects, plus some human voices mumbling from

time to time, but it is presented without any narration.

I draw

your attention to this two minute

sequence. Have a good look at the shots as they now appear, without audio, and

see what conclusions you draw from them.

I’ve

made some notes concerning these images as one would do in an editing room when

making a shot list:

0.00 A man playing with a dog, other dogs in kennels, still on board ship.

0.15 A

wide shot with the ship in background, men and dogs running playfully in

foreground.

0.26 Putting the dogs into harness for pulling

sleds.

0.40 Dogs pulling sleds though crevices in the ice.

1.02 Dogs and sled on flat ice.

1.25 Man playing with a dog, lifting a dog off the ground.

1.35 Four pups eating.

1.39 Happy man with PIPE, playing with four pups.

After

you’ve thought about this mute assemblage of shots, and also

my descriptive notes, consider what you might add to them. Then play the same

sequence again with its audio track

I

think you will find that these two versions, the first without audio and the

second with audio, have a substantially different impact upon you as observer,

what you make of them, what you feel about them.

Let

us take this one step further, these same images have been used in the Nova documentary

called “Endurance”:

This

is almost the same sequence as shown in the mute images, but beginning with the

shot of the man jiggling the puppies. Now we are told his name is Tom Crean,

and we are told that he stole food for the pups!

If

we skip on ahead we come to the shot of a man sitting in a kennel with a dog.

His name is given as Frank Wild and he is followed by Frank Hurley bonding with

‘Shakespeare’ the “Holy Hound”.

Then

we see images of the men and the dogs, the men working to disentangle the

traces for the sleds. There is conjecture about Shackleton watching and musing.

Later

we see shots of the snow tractor with an interpretative ironic comment that it

is “easier to pull it rather than to drive it”.

What

you have seen in these different versions are pretty much the same shots used

in quite different ways. In the Nova doco they are “explained” or

“contextualised” in some respects by the narration which was probably informed

by diary entries of crew members, and also derived from recorded reminiscences

or letters of crew members written to their family members.

Each

way of presenting these events gives us different levels of information, and

extremely different emotional responses to the visual material.

Now I

want to add something which will distress animal lovers. This is not included

in the “tribute” piece made by Pete Vassilakos, I only discovered it by watching the Nova doco:

As you

see, this extremely sad sequence gives us an altogether different take on

everything which we have seen in the other clips. If you watched only Pete

Vassilakos’s tribute piece, you would have no concept of what happens

afterwards, although you may have noticed that at some point there are no

further images of the dogs.

Another video compilation telling the Endurance story shows a man with a rifle going off to kill the dogs followed by a gunshot. I can't find that sequence now, it must have come from some other version of the great misadventure. However the Nova documentary does give important background information relating to this momentous event in the unfolding of the story.:

This

extra information given in the Nova documentary is intensely moving because we

have already been told of the deep bond which has developed between the men and

the dogs; that was also clearly established in the silent footage.

But

this raises another issue when it comes to finding the truth in documentaries:

the very same shots can be used over and over, in different combinations and

sequencing. Different producers,

different script-writers and editors, will select bits and pieces of the

original footage which best suit their own intentions, or agendas. How can we

ever know what has been cut or what has been put in a different order? How can

we ever be sure that they have not introduced some footage from a different

event which is not the one they purport to display in its entirety?

The

answer is simply that we cannot be sure! Our experience of so many

documentaries derived from newsreels shot during World War One and World War

Two has shown that producers of compilation documentaries often plunder images

from other events than the ones they are describing.

CONTEXTUALISATION

I think

it’s clear from what I have shown so far that everything we see may suffer from

lack of contextualisation or from placing things in a context which is

unsupported by the material which has been selected. In the case of Hurley and

fellow adventurers of his time, their images, both movie footage and still

photographs were often presented in the form of “lectures” accompanied by still

photographs and including mooving pictures.

Depending

on whoever was the presenter, e.g., Shackleton in England or Hurley in

Australia, the same material might also have been used differently in each

case, and it might have been altered between one presentation and any

subsequent showing to improve it.

Hurley

was an inspiring person. From all accounts he had a lot of charisma and

hutzpah! He was incredibly athletic and put himself in really difficult

positions in order to get his images.

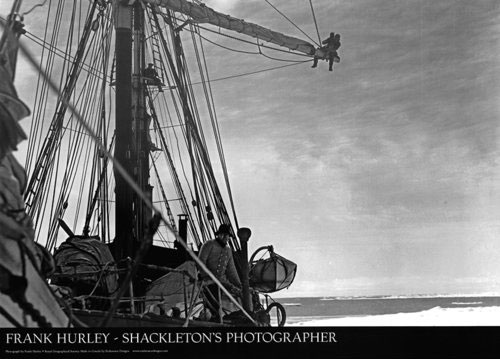

Let’s

look at this first example of some scenes of the Endurance which were filmed on her way south to the Antarctic

circle. You see the ship rolling in the big seas, the men high in the rigging

on a spar, rocking from side to side. These images must have been filmed from a

similar position in the rigging, high above the deck.

This

next photograph clearly shows the deck of Endurance viewed from high above,

camera tilted slightly downwards, a mast clearly in foreground. Where was the

camera and the photographer (Hurley) positioned to get this shot? My guess is that he was stationed on a

“spar”, the horizontal piece attached to a vertical mast which had to carry the

sail.

In the

next photograph we see Hurley clearly perched on a spar high above the deck

with his camera and his tripod quite far away from the mast, hanging over the

sides of the ship. Why was he using a tripod way up there? Tripods are usually

used to support a camera and to level it on the ground or on the deck, so why

use a tripod up on a spar? My guess is that the incredibly brave and agile

Hurley wanted the tripod up on that spar for the freedom to use his hands to

crank the movie camera. It would also permit him to “pan and tilt” his camera,

while secured to the spar and therefore freed from shaky handheld movements. I

have never been brave enough to film off the ground more than a couple of

metres and I’ve never put myself in such an uncomfortable place to get shots. I

prefer to make films in safe places wherever possible so I could never have

achieved the spectacular results Hurley got. He belongs to that tradition of

photographers and cinematographers who would go to great lengths, risking their

life and limb to get spectacular shots.

In this next

image we see that Hurley has no tripod on the spar.

He’s clearly hand-holding

his camera as he films from high on a spar overlooking Shackleton on the deck,

and note how far that spar protrudes from the side of the ship.

The

following clip presents a sequence which I’ve created from just a few shots

selected from Vassilakos’s tribute footage:

Here’s a SHOT-LIST of that demonstration sequence, or

its Edit

log:

It

begins with the ship having left Buenos Aires, now heading south to the

Antarctic, the sea ice being split apart by the ship’s prow.

From 21 to 38 secs there’s a beautiful shot

of the Endurance approaching camera, including camera stops,

(jump-cuts). The ship is still moving through water but she’s not under sail,

so she must be powered by engines at this time.

From 39 secs the ship is now trapped in much thicker ice and men are using picks

and crowbars, trying to open up a channel in the ice.

From 52 secs through to 1.20 we see men using long ice-saws, two men pushing down while

four others are pulling on a rope to draw the saw upwards after each

downstroke.

1.20 - 1.29 Some men are trying to push the ice away with long

poles.

1.30 - 1.38 A long line of men pulling a rope coming away

from the ship.

It’s

possible to form your own interpretation from these images which might be

misleading. We now view many of these same images used in the Nova assembly,

and we can see that they have been contextualised. They remain just as dramatic but

they also are given new “meaning”: and “atmosphere”:

From

2.32 - 3.04 an explanation for making the square shaped cut into the ice and

the chain of men pulling the rope which hoists up the scientist’s net. This

context is rarely explained in other films which use the same shots.

Verisimilitude

1.

the appearance or semblance of truth; likelihood;probability:

“The play lacked verisimilitude.”

2.

something, as an assertion, having merely

the appearance of truth.

I find it interesting that

this word can be used both as praise or as a put-down!

Let’s

compare the ending of the Vassilakos’s tribute

film with the TV documentary “Shackleton's

Voyage of Endurance”.

At 14.35 we saw Hurley bonding with his

favourite dog “Shakespeare” the “Holy Hound” which I showed previously.

From the 15 minute mark to the end of

the film (20 minutes) we see the arrival of the men in the boats at Elephant

Island, farewelling the rescue team as they leave for South Georgia in the remodelled lifeboat boat the “James Caird”.

There

are also shots of the men on Elephant Island waiting for the return of a

rescue ship. These are followed by Shackleton’s return in a steamship to rescue

the men on Elephant Island.

This

five minute section of the tribute film is mainly constructed from still

photographs.

It’s

lucky we have these five minutes because they certainly represent a most

important part of the entire expedition. From what I have seen in all versions,

I don’t think Hurley used his movie camera very often, if at all. No moving

pictures since the time the dogs were put down!

This “Elephant Island” period should

contain three categories of images:

a)

What occurs as Shackleton and

his small crew sail to South Georgia and land on that island.

b)

What happens with the men

remaining on Elephant Island while Shackleton is away hoping to secure rescue

for his men.

c)

And finally, seeing the men

being rescued by Shackleton returning from South Georgia.

At

20.10 we are shown images including information about Shacklton’s death, and

credits. But the film’s coverage of the expedition has really come to an end by

20.10.

Here is a short breakdown of what is

actually shown from 15 mins to 20.10:

15.10 Stills of the men landing the boats and

pulling them onto the shore. Unloading the boats, setting up camp. Food and

mugs of warm drinks?

16.34 Preparing the “James Caird” for launch

after the re-modelling which raised the height of the hull by a few inches.

17.30 Waving farewell and “safe return” to the departing men of the rescue

mission.

17.53 Making the camp more weather resistant, they have combined two boat

hulls to form a hut with a sail

covering, then we see shots of the men waiting.

19.04 TITLE: “August 1916” followed by steamship approaching.

19.16 A life-boat arrives at, or departs from shore, steamship in background.

19.38 The steamer arrives at a busy port? We are not told where that port is.

19.57 The rescued crew, all cleaned up and a much happier looking group of

chaps.

Now

dear reader, please remember, as I stated earlier, my comments are not an

attack on Pete Vassilakos’ work as his tribute film is very good. I’m merely

pointing out that so much of what is important is not addressed by such a brief

film, it simply cannot be addressed and I’m sure there are many significant

reasons for that.

Anyone

who stumbles upon that film but who does not see any other documentary works

covering this same subject would be quite unaware of what a monumental and

miraculous escape the crew lived to celebrate, and they would have no idea of

the hardships encountered by the men who went to South Georgia, nor the men who

remained on Elephant Island.

This is

where the Nova documentary called “Endurance” comes into its own:

I will

now show a few clips from this historical doco which will give you some idea of

the incredible daring of the rescue mission as well as some experiences shared

by the men who waited on Elephant Island.

What an

extraordinary expedition this was in the period of the first part of World War

1. At the “other end of the Earth” so far removed from all the terrible things

going on in Europe, a crew of 28 men fought for their lives against the great

adversary, “Mother Nature” in the icy seas of the Antarctic. They also fought

against the vagaries of temperament and idiosyncracies which would most likely

be found in any group of 28 people.

From

Wiki:

The crew of Endurance in her final voyage was made up of the 28

men listed below:

The names highlighted in yellow are the men who

sailed the “James Caird” to South Georgia.

Sir Ernest Shackleton,

Leader

●

Frank

Wild, Second-in-Command

●

Frank Worsley, Captain

●

Lionel

Greenstreet, First Officer

●

Tom Crean, Second Officer

●

Alfred Cheetham, Third Officer

●

Hubert

Hudson, Navigator

●

Lewis

Rickinson, Engineer

●

Alexander

Kerr, Engineer

●

Alexander

Macklin, Surgeon

●

James McIlroy, Surgeon

●

Sir James

Wordie, Geologist

●

Leonard

Hussey, Meteorologist

●

Reginald

James, Physicist

●

Robert Clark, Biologist

●

Frank

Hurley, Photographer

●

George Marston, Artist

●

Thomas

Orde-Lees, Motor Expert and Storekeeper

●

Harry

"Chippy" McNish,

Carpenter

●

Charles Green, Cook

●

Walter

How, Able Seaman

●

William Bakewell, Able Seaman

●

Timothy McCarthy, Able Seaman

●

Thomas McLeod, Able Seaman

●

John Vincent, Boatswain

●

Ernest

Holness, Stoker

●

William Stephenson, Stoker

Their

extraordinary story really falls into two main parts, the first part ends when

the entire crew arrived at Elephant Island, exhausted and starving. After a

period of resting the crew is split into two groups: a rescue mission led by

Shackleton with 5 other men, while 22 men remained behind on the island,

including Frank Hurley.

On

board the “James Caird”: Frank Worsley, Harry McNish, Tom Crean,

JohnVincent, Timothy McCarthy and Ernest Shackleton.

Now the

story becomes two separate stories but the only images relating to the

Elephant Island party are only still images captured by Hurley. I think he was

using a small “hand camera” rather than a large-format plate camera.

The

still photographic images showing the steamer arriving to rescue the men are

not “actualities” they were a set up: they were most likely re-enacted for the purpose of the film lectures which

would follow on return to Europe.

So all

that you could possibly see in Pete Vassilakos’s tribute film which run from

the 15 to the 20 minute mark, were stills taken by Hurley on Elephant Island.

And there are not many of those used in that film. The incredible voyage to

South Georgia and the crossing from one side of that island to the port is not

covered by any footage of any sort. That is where a dramatised documentary

comes into its own because it has so many ways of giving the viewer extraneous

information. The most obvious ones are:

A narration, formed from research of all

the records left by the men who were involved.

Interviews with descendants of the men.

Re-created footage standing in for missing

actuality footage, but made to look like Hurley’s footage seen in the earlier

part of the expedition.

Sometimes

an editor will “pinch” footage from other events and splice them into a film

where they do not belong. (Poetic licence?)

Interviews with historians.

Observational material featuring modern day

adventurers demonstrating the difficult situations which would have faced

Shackleton, e.g., taking accurate readings of the sun while at sea in heaving

waters, huge waves and wind, and almost sunless cloudy skies.

Animations of maps which indicate the

trajectory to be sailed compared with the actual journey which got them to the

island of South Georgia.

The

Nova documentary Shackleton's Voyage of Endurance (2002) uses all of the above techniques and

more, especially sound effects and music to heighten the drama of the events

which are depicted. It’s a fine piece of television documentary. I place it

right at the top when it comes to documentaries which present historical events

for TV audiences. I can’t vouch for its absolute accuracy, but it certainly gives the impression that it has been rigorously

researched and scripted and that it tries to depict the events “truly”, even

when it uses dramatised reconstruction to represent what could not have been

filmed at the time. It feels “authentic” all the way through.

Although

I had seen “Shackleton” the film starring Kenneth Branagh previously, in

many respects I preferred the Nova doco. Why do I think the Nova doc on

Shackleton is so much better?

It’s

more thorough, it gives overviews, it gives the viewer many important details.

It is a bit sentimental and romantic in its portrayal of heroic status, but it

does not wallow in sensationalism. It’s not mushy. It is also critical when it

needs to be. But the overriding impression I took from it was it has the appearance of being as truthful as

it could be to the subject, from small details to the broad scope of the

whole endeavour and its place among the actions of the world’s nations

during WW1. The feature length drama Shackleton with Kenneth Branagh

playing Ernest Shackleton is also a fine piece of work, but I won’t discuss it

from here on because it is a fully dramatised film of an

historical event, whereas I’m concentrating on the genre of “historical

documentary” in this essay.

What a

sequence this is! Shackleton knows how difficult the boats will be to move when

fully loaded with necessities and like a good military commander he supervises

the “culling”. He probably upset McNeish deeply by refusing him permission to

build a smaller boat. In any case these two had a rocky relationship that

worsened as the crisis deepened.

Then

there’s the trouble between him and Hurley. They both knew the importance of

the images which Hurley had so painstakingly captured along the way but the

plates would be just too bulky and too heavy. As a filmmaker I can imagine how

distressing it must have been for Hurley, but really, so could anyone who has

lost family photos and films which are destroyed by fire or some other

catastrophe.

But

what about Shackleton making sure by supervising the

destruction of the plates which were to be left behind. What a vital piece of

information! It speaks volumes.

Trust:

A centrepiece of the Nova documentary’s themes!

So, how

many different sorts of documentaries are there?

Do all

the films and videos which go under that heading deserve to be there?

Which

of those I’ve already mentioned really are documentaries? Or all they all just

different types of documentary?

Is

there a difference between a documentary and an actuality?

What

constitutes an “actuality”?

I’ve

tried to address this issue in two previous essays:

http://www.innersense.com.au/petertammer/1896.html

and

http://www.innersense.com.au/petertammer/flaherty_hurley_1.html

What do

you do when something which purports to be a documentary may be nothing but a

fictional piece of work which looks like a documentary?

Or when

a film is truly observational, but when the subject matter changes under the

scrutiny of the camera?

Let’s

jump to some more recent examples which are well known. Take the Maysles

Brothers. I’m selecting my two favourites now… “Salesman” and “Grey

Gardens”. Are either of these films really documentaries? What I can

say about each of them is that they are definitely observational films which

“portray and intrude upon” the lives of their subjects. The subjects were compliant

with the filmmakers, but in Salesman the central character

starts to fall apart under the scrutiny of the filmmakers. There are also

moments in Grey

Gardens where elder Edie seems to be about to fall apart, out

of the film, but she hangs in there. Younger Edie plays the filmmakers to the

hilt.

Getting

back to Shackleton and Hurley… there are many images which Hurley took which

are clearly “set-ups”. You can spot these images immediately, situations where

it’s clear that he could only have got the picture if people performed for him

upon request. There are others which are more “casual”... where action is

happening, unfolding, the men are busy and all Hurley has to do is to be ready

and on the ball to get the shot. And then there are some in which Hurley is

being filmed as a crew member, which he probably set the camera for and asked

another person to operate the camera for him.

Should

we make any distinction between these types of images as being more truthful or

less so if they were set up for the camera, specifically performed for Hurley

rather than occurring naturally? If we were to reject set-ups as “lacking

validity” and not use them in an edited version of the work, the resulting

movie would be extremely brief. Some events can only be represented if they are

“performed upon request”. It would be virtually impossible for someone like

Hurley to lug all the camera equipment around and always film things only as

they occur. Even with modern highly portable equipment this is still the case.

Some

events are premeditated… the camera operator knows that the dogs are going to

be offloaded from the ship, sliding down a sail to the ice. So he selects the

camera position knowing that this event will occur soon enough, he can capture

it if he is prepared for the event. His only direct involvement in the action

is in signalling that he’s ready to film before they release the dogs.

Another

example similar to this is when the men are sledding through crevices and you

can see the dogs and the sled with the man behind it approaching camera. How

can Hurley get such a front-on shot if he can only record what is already

happening? Well, if there are three sleds going in a similar direction, if he’s

quick enough he can see that the first one has done such and such, so he may

hold up the second or third until he’s got the camera ready. With extremely

cumbersome equipment in such harsh icy conditions these sort of images are

always going to be difficult to capture even as still photographs, let alone as

moving images which may require “following” i.e., panning and tilting while

cranking the camera with a crank handle like a coffee grinder. These days when

all our new technology is so light and so brilliant giving us superb images

effortlessly, we still have the dilemma of how to capture events if they could

not be “repeated for the camera”.

Another

stream of criticism often levelled at Hurley is his “artifice” in tinting his

images, giving them some sort of hue additional to the

Black&White of the old film-stock. That is, he is considered by some people

to be manipulating the viewer’s response by giving a picture a bluish tinge, or

an orange tinge, rather than leaving it black, grey and white. These techniques

were becoming more common among moviemakers of all classes at that time,

indicating perhaps a “yearning” for colour and the emphasis of the moods which

such colour washes give, either a warmer or colder feel.

Looking

at those two images now, more than 100 years after they were created, I feel a

deep sense of enjoyment, appreciating them for their beauty which I’m sure

Hurley was striving for at the time. I’m also confident that he felt the “hue”

gave the images a more “naturalistic” impression than monochrome could give.

Then we

come to “superimposition” where the photographer can create an effect by

combining two images in the same print. This is much more easily achieved with

confidence when combining still images in a darkroom. But it can be done with

movie film, either by optical printing or by staging a double exposure as Méliès did in his

film “The

India Rubber Head”. That would be extremely difficult for Hurley to do

with his movie camera in those conditions unless he accidentally filmed over

something he had already shot before developing the negative, or unless he used

optical printing later in the post-production phase.

As I

can’t find a clear example of this technique from his Antarctic expeditions I have

chosen to represent it from his AIF images in WW1.

Hurley

was castigated by many critics of his time for employing the whole range of

“tricks” in what people expected to be “true” documentation, as if the truth

could only exist without adornment or manipulation.

My friend Andrew Pike has written about this here.

This

criticism of “FAKERY” has trickled down to our time and you can see that bias

clearly in the following article published in The Guardian 2004. I regard the headline as seriously biased

encouraging the reader to assume that Hurley was some sort of fraud. However

the tone displayed in the headline is not the same as the tone of the following

text:

Shackleton expedition

pictures were 'faked' | UK news | The Guardian

https://www.theguardian.com › World › UK News

Aug 21, 2004 - Shackleton expedition pictures were 'faked' ... They are the photographs

that show what is perhaps the greatest story of endurance and valour ever told, the epic ... Hurley's frequent use of

'artistic licence' was confirmed this weekend by ... of the footage from Antarctica in Sydney,

Melbourne and Adelaide.

My own

view is that Hurley felt he was entitled to do any and all of these things

because they were all part and parcel of what a photographer could do and they

were all viable techniques just like framing, panning or tilting. He would have

had some familiarity with selective focus: either “pulling focus” or selecting

one plane of focus so that only one part of a shot was sharp and the rest a bit

soft and fuzzy.

Let me

put a contentious argument here: if Hurley was to film a scene below deck on

the Endurance before the ship became icebound and if he added some artificial

light to enable the image to be caught, would we call that a fake?

In my

own filming in Indonesia I was filming in a Batik factory in Java where two

styles of Batik were being created. I had to resort to a “trick” to enable me

to get the shots of the “stamped” Batik technique because the light level in

that part of the factory was extremely poor and my battery light had lost power.

The only way I could achieve my images in that room was to record at 8 frames

per second instead of 24 FPS. I asked the women to go very slowly, which they

did, and I got a sequence which would otherwise have been impossible or very

poor. Was that “faking it”? By the way, no-one ever picked my effort there and

I never had to suffer any critical attack for employing that “trick”.

I’m

also confident to assert that Hurley did not see himself as a “scientific

recorder” like Muybridge with his “grids” placed within shots to register

images with “precision”. I’m sure that Hurley viewed himself as an artist, a new

kind of artist who had cameras and a wide range of photographic

techniques available to allow him to create images which would have emotional

impact upon the viewer, whether in a gallery, a cinema, or merely attending a

“presentation” lecture which included slides and movie footage.

I’m

full of admiration for Frank Hurley. I think his achievements were astonishing.

As a filmmaker since about 1962 I’ve experienced many of the issues facing

Hurley in far less demanding circumstances. I have never had to film in the

harsh Antarctic environment with all its attendant physical demands, let alone

the sheer dangers, the extreme hardships and exhaustion that these men endured.

Hurley with two different cameras he

used in the Antarctic expeditions.

It’s never easy getting shots to look

the way you would like to have them.

I often

think of those intrepid people who make films of mountaineers. How in the world

do they make a film in those situations when most of us could barely climb

those rockfaces with the climbers who are the subjects of those films?

Fortunately I have never been required to climb a mountain let alone film those

events with climbers as they progress. I’ve also experienced the huge problem

of large, heavy, clunky cameras such as were available to Hurley and his

contemporaries.

|

movie camera but it was far

too heavy and clumsy for me.

I endured that camera for

months and when I let it go

|

So we can’t deny the fact that Hurley staged many of his memorable stills and moving images, and that he embellished them with various techniques such as double exposure, adding hues, etc. These “tricks of the trade” were later called into question by people who rejected his right to create images that would intensify emotional responses in his viewers.

How

dare he be so bold!

Peter

Tammer

October

26th, 2019.

see also:

The Search for Truth in Documentaries

Part 1: Robert Flaherty & Frank Hurley

Part 3: Robert Flaherty and Nanook of the North

NOTES:

The NOVA DOCO: Shackleton's Voyage of Endurance (2002)

This link is for the Nova Doco, but only for the shorter 2 hour 6 min. version.