It has taken me a long time but finally I’m

onto Nanook and Flaherty. I had been planning to write this chapter for three

years, but what’s three years compared with the one hundred years which have

passed since Robert Flaherty set out to make the Big Aggie? Yes, he started

filming in August 1920 and completed it in August 1921. I’m still trying to

come to terms with this film Nanook of the North which I first

saw at the age of twenty when I worked in the information section of the State

Film Centre in Melbourne.

Many wonderful films were available to me at

the time but two which made a most profound impression were “Nanook

of the North” and “Pather Panchali”. I was very

fortunate that these films were available to me when I was only 20 years of

age. I’ve seen them many times in the years which have slipped by since then. I

showed both films to many student groups when I taught filmmaking at Swinburne

and the Victorian College of the Arts. I recall a screening about 1997 when I

introduced Nanook to my VCA doco students. I told them that although the

film was made about 1920 “...it’s still

as fresh as a daisy”. I also told them that ‘documentary’ might be a

misnomer.

As I mentioned in Chapter 3 Flaherty set out

for Hudson Bay in 1910, prospecting for iron ore magnate Sir William Mackenzie

who suggested that Flaherty should take a Bell & Howell movie camera with

him on one of those expeditions. This clip from the introduction to the film

shows a map of the area:

Flaherty shot a lot of footage over the two

expeditions. 70,000ft is mentioned in some accounts. When he returned to the

USA he edited it and showed it around, but he had an appalling accident when he

dropped a cigarette into some nitrate film in his editing room and lost a huge

amount of his negative. This photograph taken later in his life shows he had

still not given up smoking:

He still had a positive copy left over from

that disaster which we would call a ‘cutting copy’ or ‘work print’, i.e., a positive copy struck from the camera negative to enable editing of the

footage without harming the original negative. He showed this positive cutting

copy in various screenings while he considered what he might do with his film.

According to the introductory graphics at the

head of the film he was not pleased with his footage, he states: “It didn’t amount to much!”

I imagine from what he said in those captions

and from what others have written that he found it too fragmented, lacking a

thematic throughline or themes. It’s possible he already knew that he needed a

central character, maybe even a hero. From the outset I believe Flaherty was

not trying to make an ‘actuality’ film as the Lumière Brothers did when they made “Workers departing the factory” or “A

Train arrives at a station”.

I think Flaherty's motivation was to make a ‘mythic’ film that would present a passing way of life which could not easily be

captured with the limited technology of his day, also considering the extreme

conditions he had already experienced in the frozen wastes of the arctic

circle. Returning from those earlier expeditions where he had tried to capture

an actuality

observational film he was quite disappointed with the results it makes

sense that his next attempt might be a representational film.

From 1916 he set out to make the film we know

as “Nanook

of the North. He spent many years trying to raise the finance and

eventually succeeded in obtaining the funds he needed from Revillon Frères, a French fur trading

company. Some reports say he undertook a course in filmmaking in the period of

1913/14. I don’t think that happened then. I think he would have needed to

learn much more about the Akeley camera which was quite

different from the one he’d used in the past. There are different reports about

when he took this course, some say 1914, others say after he’d secured the

finance for Nanook. I suspect it was the latter, preparing for the major

shoot in 1920. Perhaps he took a course on both occasions!

From WIKI:

“He bought two

Akeley motion-picture cameras which the Inuit called 'the Aggie'. He also

bought full developing, printing, and projection equipment so he could show the

Inuit what they had filmed on location. He lived in a cabin attached to the

Revillon Frères trading post.”

The two images below show the model of Akeley camera he used with two different lens configurations. The first has short

lenses such as we would now call a “normal” lens. In 35 mm this would be about 50 mm focal length and would present images in what we would call a ‘normal perspective’.

The two lenses you see on this camera are identical.

The lens on the right allows the light to pass to the film plane.

The lens on the left

side is for the operator to frame shots

via the rectangular tube

on the side of

the camera above the crank handle.

Parallax viewing is never

really accurate for framing.

Then Flaherty set off to the Hudson Bay area to

make the film with his new equipment and his improved technical knowledge. He

chose an Inuit man called Allakariallak to be the central character, re-naming him "Nanook" which means “Bear”.

He thought that name would make it easier for people to relate to his central

character yet still remain in touch with Inuit culture. Two Inuit women played

Nanook’s two wives, but they were not Allakariallak's wives.

You can sense where I’m going with this line of

thought. He intended to make what we would call a narrative-drama which would represent the lives of the Inuit as

he knew them from previous trips, not an ‘observational’ film. Now I’m not

saying there is no observational footage in Nanook of the North. I’m

certain there is. But it’s only a small percentage of the footage in the film,

by far the greater proportion being ‘set-up’ or ‘dramatised’ material. If you

like, ‘fake’ observational footage. Take a look at this extremely significant

scene filmed at the Trader’s store:

Nanook is seen listening to the voice coming

from the phonograph. He appears to be hearing it for the first time and he

actually bites the record to taste it. Like many other scenes in the film this

is pure pretense. It’s not ‘actuality’ footage of Nanook doing something spontaneously for the first time when

the camera just happens to be rolling. It’s acted and it’s directed, and it’s

pretty good acting too.

You can see why many people from different eras

might be confused about this film. It was controversial when it was first

released to the world in 1922 and it remains controversial down to our time.

Here are some comments by critics of the film:

Visit to the

trade post of the white man

From Wiki:

“In the 'Trade

Post of the White Man' scene, Nanook and his family arrive in a kayak at the

trading post and one family member after another emerge from a small kayak,

akin to a clown car at

the circus. Going to trade his hunt from the year, including the skins of

foxes, seals, and polar bears, Nanook comes in contact with the white man and

there is a funny interaction as the two cultures meet.”

“The trader plays

music on a gramophone and

tries to explain how a white man 'Cans' his voice. Bending forward and staring

at the machine, Nanook puts his ear closer as the trader cranks the mechanism

again. The trader removes the record and hands it to Nanook who at first peers

at it and then puts it in his mouth and bites it. The scene is meant to be a

comical one as the audience laughs at the naivete of Nanook and people isolated

from Western culture. In truth, the scene was entirely scripted and

Allakariallak knew what a gramophone was.”

“In making Nanook,

Flaherty cast various locals in parts in the film as one would cast actors in a

work of fiction. With the aim of showing traditional Inuit life, he also staged

some scenes, including the ending, where Allakariallak who ‘plays’ Nanook and

his screen family are supposedly at risk of dying if they could not find or

build shelter quickly enough. The half-igloo had been built beforehand, with a

side cut away for light so that Flaherty's camera could get a good shot.”

I had known from my earliest viewings

that some scenes were ‘set-ups’, e.g., when examining the "family bedding

down in the Igloo" scene. As a filmmaker I knew that Flaherty would have

struggled to get a ‘wide shot’ inside an igloo and also that he would have

struggled to get enough light there as film stocks were very slow in those days, meaning not as light-sensitive as they became many

years later. Also, lenses of that period were also ‘slow’ meaning not permitting filming under low light such as

modern lenses do. At that time lenses could not ‘open’ to an aperture

more than f.2.8, while a few years later they could open to f.1.4 which is two f. stops faster. A lens opening of f.1.4 allows you to capture an image with ¼ the intensity of light which would be

required for an aperture of f.2.8.

I was also doubtful that he would have

had a really good wide angle lens and

the shot inside the igloo shows no typical wide

angle distortion. I was not too surprised when I read that he had built an

extremely large half-igloo to avoid all those difficulties. Otherwise he simply

could not have achieved that scene at all.

Hunting the Walrus

From Wiki:

“It has been pointed out that in the 1920s when Nanook was filmed

the Inuit had already begun integrating the use of Western clothing and were

using rifles to hunt with rather

than harpoons, but this does not negate that the Inuit knew how to make

traditional clothing from animals found in their environment and they could

still fashion traditional weapons. They were perfectly able to make use of them

if found to be preferable for a given situation.”

“The film is not technically sophisticated; how could it be, with

one camera, no lights, freezing cold, and everyone equally at the mercy of

nature? But it has an authenticity that prevails over any complaints that some

of the sequences were staged. If you stage a walrus hunt, it still involves

hunting a walrus, and the walrus hasn't seen the script. What shines through is

the humanity and optimism of the Inuit.” (Roger Ebert)

So let’s have a look at that sequence:

The many criticisms raised against this

sequence seem very strange as I’ve followed them as an active filmmaker from 18

till now at 77. When I first saw Nanook I saw a muddy 16mm print but

I didn’t know then that it lacked clarity until I saw much better quality

copies quite recently. And I’d never seen a film quite like it at the age of 20

even though I had seen hundreds of notable films by that time.

I didn’t view it again until about 1986 and

then I saw it with very different eyes from when I was only 20. I saw things as

a filmmaker with more experience which had escaped me in 1963. But I did not

see the gun! How could that be?

From 1986 I showed it to many groups of my

students up to my retirement in 1998. None of them mentioned the image of the

gun. Recently I noticed it was carried by the trader. I had not even noticed

that the trader was one of the hunters in any of my previous viewings.

Now you might wonder why I missed this gun?

Partly because the older copies were unclear 16mm prints, partly because I was

concentrating on other things. I was probably concentrating on the plight of

the harpooned dying walrus. I was aware that images of the Eskimos creeping up

on the beached walrus herd were filmed in telephoto because I could see how compressed the perspective was: it was typically

telephoto. I could also imagine why

Flaherty used a telephoto lens for that sequence because the camera would have

made a noise like a chaff-cutter so they were forced to keep it a good distance

from the herd so as not to frighten the walruses away.

In later viewings I saw the rifle in the hands

of the trader, both before and during the hunt. That was probably on my 15th

viewing of the film! How could I be so slow? That raises another question: did

they actually shoot the walrus with the rifle and if so when? Did they shoot

the walrus close to the time it was harpooned or only after it was harpooned,

perhaps to shorten the pain of its death throes? If so, I applaud them.

And, of course, “So what!” So what if they used

the rifle in the hunt as well as their traditional harpoons, because this film

was clearly shot in a period of transition between the ancient

unspoilt Inuit culture and the modern colonial trading intervention, long

before what it is today with motorised sleds, etc. Flaherty was making a film

which represented changes to the Inuit way of life during that transitional era

which included their original culture as well as their adaptation to European

trade and technology, as has so eloquently been pointed out in the Wiki quote

from Roger Ebert.

But the heart of the matter comes down to this:

not only was I fooled by my earlier viewings of the film to see less in this sequence than I have seen in more recent viewings, but I think that was

the same for many of the people who saw it on its first release when it created

a sensation.

Why have these criticisms been raised to the

level of ‘controversy’ to denigrate such a great work? Why does this happen

over and over in cinema history? Is it just the shock of the new similar to the

furore at the premiere of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring in 1913?

The denigration of Nanook of the North extends to many other scenes in the film. It seems that people desperately

wanted to belittle or undermine the wonderful qualities of this beguiling

masterpiece. Why did they feel the need to do so? Fortunately for people who

revere the film it’s so great that it rises above these carping criticisms and

is rightfully placed among the great works of cinema.

Let’s take a look at a different kind of scene

altogether, something which probably was observational in nature, Nanook icing his sled runners to prepare for a

new day’s trekking:

You can see from the way this scene is shot

that it is more casual and ‘perfunctory’. It gives information which is

intended to explain conditions in the icy wastes, difficulties which the Inuit

must endure and overcome, including protecting a sled made of organic material

from the hunger of the dogs, while also warming their own hands when icing the

runners with the cold water. It also explains the necessity of protecting the

young huskies from the hunger of their elders.

It’s such a brief sequence. It has all the

hallmarks of ‘actuality observed’ rather than set-up and performed filming. It

could be considered as ‘filler’ or it could be considered as ‘essential to the unfolding narrative’. I

think it’s essential for many reasons: it gives us some necessary information

about their daily routines and it backgrounds the importance of those routines.

It also speaks to the harshness of the conditions which threaten the lives of

these people, even in an era of transition when they can trade skins for metal

pots and tools from the trader’s store. It also shows how they have to look

after themselves with the cold biting into their hands, warming their freezing

hands on their cheeks just as we might do when we visit ski resorts.

There are other small vignettes in the film

which have this quality of information fill-in. This scene shows Nanook sewing

hide onto his kayak frame:

This scene of hide being attached to the kayak

frame lasts only 20 seconds! How

extraordinary that Flaherty gives only 20 seconds to such a crucial piece of

activity and information. A miracle of invention and construction, the kayak is

central in the lives of these hunters as viewers will see in other sequences.

Then we are shown the ‘omiak’ or large canoe being

carried by many Inuit from the river to the trading post.

We are told its frame is made from driftwood

and covered with walrus and seal hides, but beyond this there is scant

information about the construction of either a kayak or an omiak. From the 1.22

mark you can see clearly how the edges of the hides do not always reach the

frame of the omiak.

At 1.42 they beach the omiak near the trading

post. At 2.29 they start hauling it up the slope where fur pelts are seen

hanging on drying racks. This omiak is quite heavy despite being made of

relatively few pieces of driftwood. This is a communal vehicle, quite

distinct from the kayak which usually serves one person, but not always as we

shall see.

I always wanted to know how they managed to

make these two flimsy craft waterproof. How come they weren’t bailing out excess

water all the time? No information like this can be found in the film as

Flaherty was not making an instructional film on “How to build a kayak or an

omiak”. I wonder if there is a documentary available on that subject?

(OK, you’ll be pleased to know such information is currently available on many

sites on the net.)

Although his film was confused with being a ‘documentary’, whatever that term

might have meant in 1922, it was not primarily intended as an information piece.

Nanook

Goes Fishing

Next we see a sequence which brings together a

lot of things I’ve mentioned so far.

This scene opens with a title which tells us

the importance of Nanook’s skills as a hunter when times are tough and his

people are facing starvation. Then we see him paddling his slender leaf-like

kayak to take him to a spot where he will fish on the ice-floe. That’s followed

by a sequence of shots which show him using a wicker mat which he uses to protect himself from the cold

ice while fishing.

This shot also raises the question

whether Flaherty used

two cameras when filming on that day.

Then we see him using a lure and a

three-pronged harpoon to catch fish which he kills by biting them behind the

head. Like any proud fisherman he shows off his large catch gleefully at 4.42.

Then he packs up for the day and gives another Inuit man a lift home on his

kayak, lying face down upon the catch of fish which Nanook had caught.

I love this sequence. It has been set-up but

looks casual. The catching of the fish is entirely dependent upon chance, he

doesn’t get all the ones he goes after but the camera observes every move

including those that got away. There are wide shots, medium shots and close-ups

in this mix finishing with Nanook giving a “brother fisherman” a lift. The

final shot with fish draped over the front section of the kayak is what we might

call “medium wide”.

Many components feed into this sequence. We see

how traditional Inuit hunters used their tools, artefacts and weapons to hunt

for fish. Their lives are dependent upon these artefacts and their skills as

hunters. We can see that Flaherty has planned the structure of this scene, it

has a beginning, a middle and an end. I’m guessing here, but I think even the

“tag” of giving a fellow fisherman a lift was not serendipitous, it may have

been planned before the shoot. In any case it doesn’t matter much about that,

it could go either way. But I’m quite sure that Flaherty and Allakariallak knew exactly what Nanook had to do that day and had

worked it out between them before they set out for the hunt.

All is not what it

seems!

In the next beautiful sequence Nanook discovers

a seal’s breathing hole and we are told that seals have to surface every 20

minutes to breathe so they must keep their breathing hole open.

1.20: We

see Nanook in profile waiting for signs of the seal arriving.

1.29: He

has his harpoon poised ready to strike.

1.30: He

plunges his harpoon into the seal (it’s a front-on shot) and then it cuts to a

wider profile shot of him struggling to hold the cord in his hands. This is

followed by a series of “antics” as he struggles to keep hold of the seal.

2.27: He

seems to be getting the upper hand and can pull away from the hole, only to be

dragged back towards the hole in the ice.

3.04: He signals to people in the distance that

he needs help. More falls, and now we are closer on Nanook. Nanook draws back

from the hole again as people arrive with a sled. They seem to be taking their

time! Another great wide shot.

4.12: We now have four assistants on the spot

ready and willing to assist.

4.30: Nanook reaches for his knife and starts

widening the hole in the ice.

4.47: We see the seal being dragged up from the

water by the entire group.

5.00: We read a caption about the dogs howling

their typical wolf howls in anticipation of a feast. Shots of ferocious hungry

dogs demanding some food. Definitely not acted. This is the real thing.

5.40: Now the entire seal is out of the hole

and up on the ice.

5.53: The butchery commences with the cutting

of the skin. Slashing through the blubber while the dogs make very fine

snarling cutaways.

6.54: Now the blubber has been peeled off and

we see the relatively skinny little carcass of the seal.

7.12: Nanook drags the skin and blubber away

from the carcass.

7.25: They roll the carcass over and start

cutting the meat. Now it’s time to carve the fresh warm meat and have a feast,

including the dogs who have all been acting as cutaways throughout this event.

These dogs are not a bunch of extras, they are central to the action. Who needs

meat to be cooked? Eating it raw sure saves on electricity and gas. Or in the

Inuit's case dried moss for fuel. But what if you can’t find enough moss to

light a fire?

8.05: Another caption about the importance of

seal meat for sustenance. It also explains that the eskimos savour blubber as

we do butter. This is followed by a shot of two children wrestling over a seal

flipper, each of them has an end of it in their mouth.

9.24: Now it’s time for the dogs to get some of

the kill. Nanook throws them pieces of meat which disappear down greedy gullets

at the speed of light. Up here in the icy waste you can’t afford to be slow off

the mark! Some dogs don’t like other dogs getting anything. So now there’s a

dog fight. Nanook separates the dogs; the final caption for the scene tells us

it’s getting dark and the dogs have caused a dangerous delay.

As you can see, this sequence has so many

elements including a lot of information.

But is it primarily an information piece? No! It could be considered as an

ethnographic documentary but I don’t think it is that. It is also very

entertaining. Every time I’ve shown it to people they have chortled along with

Nanook’s struggle to hold the seal. Then they pause when the Inuit are shown

eating the raw flesh. This whole scene is a planned, dramatised and

choreographed sequence which includes information and discomforting reality.

But all is not

what it seems.

Somewhere in the deep past I read that Nanook

was pulling on the rope which went to another breathing hole some distance away

which had a number of his friends pulling in a tug-of-war against him. If this

is true then it clearly shows that Flaherty had a very liberal sense of what is

true. He wanted to show a titanic struggle between man and beast and perhaps

that’s how he achieved it.

And behind that

story there is another story.

When Flaherty was making the film he developed

his camera original negative footage

in the cabin attached to the trader’s store where he had darkroom facilities

for developing the camera negative,

drying it, putting it through a printer to make a copy, and then developing

that printed copy. After drying that printed copy he could show the eskimos

the scenes that had been shot the day or so before.

The story goes

like this: when Flaherty was showing the eskimos the footage of Nanook

struggling with the seal they went up to the screen to try to assist Nanook in

his dire effort, having forgotten (apparently) that they were at the other end

of the rope only a day or so previously.

That reminds me of a scene from Godard’s “Les

Carabiniers” but let’s not delve into that one right now.

Where can we find ‘Truth’ ?

Is Flaherty being fraudulent when he

creates a sequence which purports to show something as “actual” when it is in

fact a “representation” or “facsimile”?

As I’ve mentioned earlier, it seems Flaherty

wasn’t interested in how to build a kayak or an omiak. But in the next sequence

he has Nanook build an igloo. This might be the most famous igloo in the

history of the world. It is certainly archetypal. It could also have been shown

in a series of How to… films such as we held at the State Film Centre in 1963.

Our motto was:

“Films With A Purpose!”

I’m not going to describe every move in this

sequence. If you haven’t seen it, it’s definitely worth a look. It runs about 8

minutes in total. I’m just going to make a few general comments about it.

The family arrive with their sled and dogs at a

sloping site and Nanook starts looking for the right sort of ice, prodding with

his spear. He finds the right stuff and starts cutting into it with his blade.

We are not told whether this blade is metal or ivory. A caption tells us that

it is “deep snow packed hard”.

Then in beautifully framed shots Nanook seems

to be instructing others where to place the dogs. He starts cutting into the

packed snow so that the cavity will be part of the structure when complete.

Another caption tells us the blade is a walrus ivory blade. This is

important because it would have different resistance to the cold than a metal

blade of similar size about as long as a machete.

We’re told it is instantly glazed with his

saliva when he licks it with his tongue. While the father works the children

play, sliding down the hill, a rather ancient game I think, one child using the

other for a sled or toboggan.

Nanook manoeuvres large chunks of cut ice into

place making a dome. The walrus ivory blade is a great tool absolutely perfect

for all the tasks which he performs. Cutting, shaving, shaping the blocks so

they fit well together.

Another caption tells us that the women fill

the gaps with snow to keep out the wind, no mortar is required. No spak-filler!

Babies hide inside their mother’s furry hoods for warmth while all the adults

work on this igloo. It’s a family job.

The children play with toy sleds, one of which

is pulled by a husky puppy. They start ’em young!

Now Nanook reaches the top of the dome, the

snow-bricks have to be cut precisely. He employs gravity assist in building this dome as all things incline towards

the centre like a keystone in an arch.

More gap-filler while the baby sleeps on mum’s

shoulders as she works. Nanook places the topmost “brick” and now we have a

perfect igloo. Final gap-filling.

Another caption “Complete within the hour!” Is this really true? Was Flaherty having a joke on us? Did these three adults

really build the igloo in an hour?

From inside the igloo Nanook cuts a rectangular

hole and sticks his head out smiling profusely, very pleased with himself. Just

a bit of over-acting here!

Then he goes looking for real ice because he’s

going to make a window to let light into the igloo for Nyla. He selects and

chips out a block which is quite different and much heavier than the blocks

which he chose to build the igloo from and he carries it to the dome.

He places it against the dome and measures it

to cut out a piece of the wall. When he has extracted it he fits the ice in its

place, smooths it off, and uses the piece he removed to make a reflector to

improve the lighting inside. The final shot of the scene shows Nyla cleaning

“her new window” from the inside.

My thoughts about this sequence: this igloo

would have astonished Brunelleschi! His

dome could not have been built in an hour but I bet he would have been

gobsmacked by Nanook’s dome. Second, every element of this dome is water! Okay,

it’s water in solid state! But it is a home made of water which will

protect this family from the biggest Arctic gales. It might get snowed over but

it will never collapse.

Then we come to the filming. There are so many

different choices of angle and view. It looks like “casual observation” but it

clearly follows a plan. I think Flaherty had seen this construction process

previously and had worked out a plan to show all the most important details. He

also gives us essential information such as the ‘walrus ivory’ blade but does

not tell us why not use a steel

blade; they could have bought a steel blade from the trader’s store. On the

other hand I suspect the tip of Nanook’s spear which he used to chip away at

the ice is metal, but I can’t be sure.

So this sequence has many characteristics aside

from the cutaways of the children playing childish games which occur everywhere

across this planet. Every element he includes in this sequence has its own part

to play in the whole, and the igloo is going to be crucial to the ending of the

film, but I’ll save that scene for last.

Who

exactly is this Nanook?

Now I’m going back a way, to the very beginning

of the film. After Flaherty’s intro which includes the history of his earlier

trips and motivation for making his new film, we get to see two wonderful

portrait shots, Nanook and Nyla. In style they are quite different from each

other.

This famous still from the film is taken from

the movie image portrait of Nanook

seen between 0.16 - 0.27. Although it’s a portraiture

shot it is a moving image, and it is acted and directed. Nanook is clearly

taking instruction from Flaherty and his weathered face shows he has had a very

tough life. He seems to have suffered an injury to his left eye.

Nyla, the smiling one, (0.29 - 0.40) is the

nymph. In the film she is seen rocking and smiling and also responding to

direction from behind the camera.

We now view the very first “sequence” of the film, Nanook

paddling from the distance to the shore in his kayak:

We are told Nanook is coming down river to the

Trading Post. A child lies facing Nanook on the front end of the kayak. He

“parks” the kayak carefully, alights from the kayak and lifts the child “Allee” off the kayak onto the rocky shore.

Then we see Nyla emerge from inside

the kayak. Wearing all those furs it’s a tight fit and not easy for her, but

she does eventually get out and onto land. Then Nanook passes the bare-skinned

baby which had been left behind to Nyla.

Now Cunayou emerges from this mighty ship.

She is no child, she’s a fully grown adult. She runs to shore.

The last to emerge from this ‘troop-carrier’ is

little Comock, a husky puppy.

Okay, that’s how it unfolds. Every time I’ve

shown it to a group of people they have all laughed along with it, full of

acclamation at this lovely sequence. Last year I showed it to a group of

elderly people, oldies like me, in Gisborne. None of the 24 there had ever seen

this film and only one of them had

heard of it before, but they all loved this film, and like me, they were

captivated from the very first scene.

However, none of them questioned very deeply

how it could have been achieved. And let me be honest, only after about 10

viewings of this film did it occur to me that it was a gag, a set-up, and quite

an elaborate one for the time.

Even if all those people could have fitted into

the hull of this little kayak it would have been really troubling for them,

incredibly difficult to get them inside the hull in the first place, and

extremely difficult for them to get them out.

I assumed after my numerous viewings that

Flahertty had made use of the captions telling us the names of the family to

allow him to “jump-cut” the scene. After the first child is put onto the shore,

a caption: “Allee”, we go back to

the kayak and later see the caption: “Nyla”...

then she comes forth, with difficulty.

She takes the baby from Nanook and goes to

shore, while Nanook stays there at the side of the kayak, caption: “Cunayou”. Cut

back to kayak, as Cunayou emerges, like Nyla, encumbered by her furs, and then

she dashes to shore.

Another caption: “Comock” and we see the little puppy lifted out by Nanook.

Now this is my contention: by the end of this

charming sequence Flaherty has the audience, well, audiences everywhere, eating

out of the palm of his hand. They love it. Just as I loved it in 1963, just as

all my students loved it when I started showing it in 1986, and just as those

elderly folk like me loved it last year. We were all captivated by this scene.

The scene is constructed like a good gag!

Flaherty was an entertainer. He wanted people to see his film. He wanted them

to love his film and he chose an opening sequence which took them by surprise

and made them laugh. And from that moment on the audience was his.

But we all bought it as if it was a single

take just cut up and with captions inserted to name the characters. I

don’t think so. You would need to measure the “waterline” as the emptying of

the kayak progresses, but it’s my belief that this scene was created

in stages, as Flaherty already knew he could intercut every individual

emergence with a caption.

Another thing which makes me feel that is the

case: the hull of the kayak narrows towards the front and the back end. So the

space inside is always becoming narrower, and its frame is quite delicate.

There would be a real risk that people would get stuck if they were all packed

in it together at one time.

From the very first scene of this film Flaherty

was signalling a few things to his audience: I’m going to surprise and

entertain you. I’ll introduce you to a group of people whom you will accept as

a family, although they are not a family in real life. I’m

giving them names which you will remember them by even though their real names

are quite unpronounceable, e.g., Allakariallak.

From the very outset he was telling a tale, a fictional account of the way of life of

a band of ice-nomads in a period, which as the audience would see in later

scenes, included the incursion of western culture at the Trading Post. The

scene which opens the film gets it off to a great start for all the audiences I

have viewed it with. They are always hooked into the world of the film and

the charm of the film. It sets a tone which will be sustained, although darker

things will follow. It is a curtain-raiser. Flaherty was an entertainer. But he

also was making a film which would bridge two cultures: the traditional Inuit

world is present all the way through the film as if the Trader’s shack and our

techno culture had not arrived. But each sequence can only exist because our

techno culture is already there, at the Trader's hut, the phonograph, the rifle

which may have been used to shoot the Walrus, and Flaherty’s camera upon a

tripod.

Flaherty depicts the intersection of these two

cultures,

Bedding Down

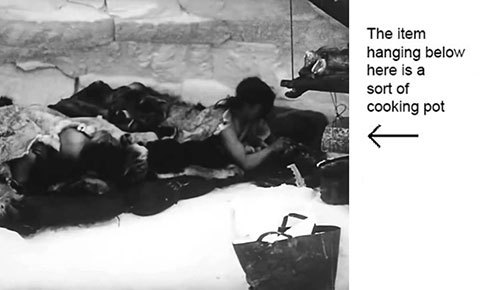

The ‘family’ is inside the igloo preparing for

sleep, the dogs are outside in the freezing arctic night.

TITLE:

“The shrill piping

of the wind,

the rasp and hiss

of driving snow,

the mournful wolf

howls of Nanook’s master dog

typify the

melancholy spirit of the North.”

When I look at the interior shots of the igloo

now I can’t believe I ever thought there could be so much room inside! The shot

of Nanook taking off his boots shows five people sitting almost side by side on

a platform cut into the ice. (0.35)

Then we see Nanook from behind, bare-backed as

he lies under some skins for blankets with the women on either side still in

their furs. The baby is also bare skinned! Now the women take off their furs

and lie underneath a thin-looking skin which covers the group like a blanket.

This is all a single wide-shot, 45 seconds duration. Shots of the dogs outside,

settling down in the biting cold. Back inside people are settling into sleeping

positions.

More dog shots and icy drifts over landscape.

Now the interior shot shows the people up

closer and from above, sleeping.

Nanook is centred.

More shots of dogs and the scudding icy waste.

Back inside the igloo we cut to a rear view of people sleeping.

Cut to Nanook seen from another angle, his face

visible, sleeping.

It’s a beautiful shot.

Very peaceful.

“Tia Mak” (The End)

Well just how large

was that igloo?

But this was not Hollywood! This igloo ‘set’

was not art-directed and created in any studio lot. It is an artificial set

which was meant to represent the real thing, but was built specifically to

permit filming inside.

Aside from that question: “How large was this

igloo in order to enable filming?” my overall reaction to this sequence is just

how poetic it is. It’s a piece of pure poetry from an era of cinema when filmmakers

allowed themselves the freedom of poetic expression. In this case the choice of

images, the quality of ‘being’ represented in those images, including the dogs settling stoically

for the long cold night outside, it’s pure poetry. But there is also a visual

rhythm to this sequence which is poetic, not just because of the musical

accompaniment.

I think the whole film is poetic in its

inspiration. It may be a very practical film when it comes to showing the

building of an igloo, or hunting for a seal or walrus, but every sequence is

imbued with a different quality of poetry in cinema. Even when it is

informative it’s also entertaining. When I say informative, that is more the

case in some scenes, less so when it comes to attaching hide to the kayak which

I mentioned earlier.

In the igloo interior there’s a shot which

shows the people using a moss fire heating something in a pot. I wondered how

this could be so inside an igloo? Wouldn’t the heat from that little moss fire

melt the interior ice of the igloo? Wouldn’t the warm breaths of five people

mean that the ice would melt and drip on them all night?

Enough of these little practicalities! The big

issue is the debate over Flaherty being a faker! Pretending to show things as

‘actual’ when they were really set-ups. Showing us an Inuit family which is not

really a family at all, just a group of individuals assembled for the making of

a film. Showing us a seal hunt which was entirely set-up! Showing us an actual

walrus hunt which included the use of a gun which may indeed have been fired to

kill the walrus, or which may not have been fired at all. All these questions

leading to endless claims of Flaherty faking it. And all these negative views

are designed to tear the film down from its pedestal.

How dare a documentary filmmaker make such a

fake film?

The controversies have been ongoing ever since

the film surfaced, not among the many who love the film and found it charming,

informative, entertaining, endearing. The negative critics had a field day and

continue to do so right down to our time.

Who are these people who so desperately want to

tear this film down?

And why are they so ferocious in their

opposition to it?

From wiki:

“As the first

‘nonfiction’ work of its scale, Nanook

of the North was ground-breaking cinema. It captured many authentic details

of a culture little known to outsiders and it was filmed in a remote location.

Hailed almost unanimously by critics, the film was a box-office success in the

United States and abroad.”

“Flaherty is

considered a pioneer of documentary

film. He was one of

the first to combine documentary subjects with a fiction-film-like narrative

and poetic Treatment. Furthermore, the film has been criticized for portraying

Inuit people as subhuman arctic beings,

without technology or culture which reproduces the historical image that

situates them outside modern history.”

“It was also criticized for comparing Inuit people

to animals. The film is considered to

be an artifact of popular culture at the time and also a result of a historical

fascination for Inuit performers in exhibitions, zoos, fairs, museums and early

cinema.”

From The Guardian:

“When the film was

released, it got rave reviews and no one

called it a documentary. It simply

seemed to be in a class by itself. It still is. Flaherty was never again to

achieve such lack of self-consciousness and purity of style, though films like

Moana, about the Samoan lifestyle, Man of Aran and Louisiana Story contained

extraordinary sequences.”

In 2014 Sight and Sound film critics

voted Nanook of the North the

seventh-best documentary film of all time.

Who said it was

a documentary? Did Flaherty ever say it was?

My friend Andrew

Pike sent me a transcript by Pat Jackson from Penguin Film (3) Review

1947. Pp. 84-87

In that article Pat Jackson

covers much more of the early history of “documentary” and the confusion which

arose over terminology pertaining to that field. You can read the whole article

by Jackson in Footnote.

Since my first viewing of Nanook in 1963 I’ve been fascinated by

the topic of Inuit or Eskimo people, not only from Canada and Alaska, but also

from Iceland and Greenland. There are many reasons for this fascination which

includes their artefacts, their way of life in such arduous conditions, how

they managed to find ways to ensure the survival of their people, whether we

regard them as individuals, families or tribes. My fascination also included

interest in igloos, kayaks and harpoons.

Just when did that term documentary come into common usage,

and how specific was that term in that period, or any subsequent period? Do you think this poster from the 1920s

suggests a documentary film? I don’t think it does. To me it suggests adventure,

entertainment and romance.

“A picture with more drama, greater thrill,

and stronger action than any picture you ever saw” !

“A STORY OF

LOVE AND LIFE IN THE

ACTUAL ARCTIC”

Nowhere is the word “documentary” present. Was

this poster just designed just to get people to see the film? Yes, I think it

was that, I don’t think it represents a change of attitude on Flaherty’s part

from when he set out to make his film to a different attitude after shooting

and editing in order to assist the release of that film.

I think it was a true statement about the

nature of the film.

Peter

Tammer ptammer65@gmail.com 23/07/2020

see also:

The Search for Truth in Documentaries

Part 1: Robert Flaherty & Frank Hurley

Part 2:

Hurley and “The Endurance”

Acknowledgements:

Many people have

assisted in the writing of this essay.

Since 2017 I've

received a great deal of encouragement from Geoff Gardner, Quentin Turnour,

Andrew Pike and Tom Cowan, all of whom are quoted in parts of the essay.

Other close friends

have made contributions along the way: Kit Guyatt, Ken Mogg, Bruce Hodsdon,

Richard Leigh. I hope I'm not forgetting anyone who has been kind enough to

read my essay and make suggestions for clarification or improvement.

However the two

mainstays all through this process have been Geoff Gardner and Bill Mousoulis.

Bill has been incredibly supportive since I first published some pieces on the "writings

page" on his Innersense site. This I can say for certain:

without Bill's continuing support I would not have much to show for the past

fifteen years!

The following article was sent to me by Andrew

Pike. It is quite relevant to a lot of the issues I’ve raised in my essay on

Robert Flaherty and “Nanook of the North”.

“YOUR

QUESTIONS ANSWERED”

by PAT

JACKSON

PEOPLE everywhere are becoming more interested

in the artistic and social questions which face the film industry. We intend to

put our readers' questions to the men and women who make our films. Send a postcard of the points you would like to

have discussed to Roger Manvell, Penguin

Film Review, Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, Middlesex. This time we have

asked Pat Jackson, director of Western Approaches, to answer a query which reads:

"More and more studio feature films are adopting documentary technique on the

one hand and fantasy on the other. Of these two powerful forces, reality and

unreality, which is the more desirable, and which is the more likely to

predominate?'

This question would be easier to answer if I

could be certain what this wretched word documentary really means. Having spent eleven years in documentary, I should know by this

time. However, there is consolation in the fact that even now film makers still

argue about what is and what is not a documentary film. Consequently I am

fairly convinced that there is no exact definition; so before answering the

question, I must try to make clear what I mean by it.

Grierson's own

definition, the 'creative interpretation

of reality,' should still serve, but somehow it doesn't, for there has been

a far too rigid line of demarcation between his type of documentary and many

studio films which, to my mind, are documentaries both in outlook and content.

This originated because Grierson's filmic interpretation of reality-through no

fault of his but the limited resources at his disposal-never had any flesh and

bones; none of the emotions which make people glow with hope and sympathy, cold

with fear and anger, or moved to tears and laughter. His interpretation could

not transmit the very breath and beat of life, because he was never able to

enter the field of drama. He transmitted information and a point of view. He

traced the outside pattern of human conflicts, but he rarely if ever could step

inside and fashion a living drama out of his designs. He found a new

subject-matter, and he taught that the contemporary scene is full of drama if

the artist has the vision and the political insight to seek it out. He revealed much of it by a

persuasive form of screen journalism. But this is not the end of documentary,

it is only the beginning.

But it was this style

which Grierson evolved that came to be classified as documentary, and I believe

that now this word has come to mean something far greater than it ever did,

something which cannot be defined by or restricted to any particular style,

technique, method or even motive of production.

When, for example, I hear one of Mary Field's Secrets

of Nature and John Ford's Grapes of Wrath both referred to as

documentaries, I feel quite justified in drawing my own line somewhere. So I

take the plunge and say here and now that to me a documentary film is one which

seriously attempts to make a contemporary comment on the way of life, problems

and true character of any people anywhere on this earth; and now may heaven

preserve me. That definition must include films of the calibre of Grapes of Wrath, Way to the Stars, The Way Ahead, Fury, Millions Like Us, Children on

Trial, The Last Chance, The Southerner and The Overlanders, and many others. To me, all these films are

documentaries, for they tell a story of people in conflict with their

environment. Parched earth, mob law, war, poverty. They have the courage to

seek out the facts, and without falsification present them in a narrative form;

they show us, not only the cause of conflict, but the effect of it on human

beings; all the facets of human behaviour and the amazing qualities of people

at grips with life and forces beyond their control. They help us to understand,

not only the world as it really is, but people as they really are and as they

become when the odds are loaded too heavily against them. They establish an

identity between ourselves and peoples of different nations. Surely, this is cinema

being used to accomplish its greatest task - the destruction of prejudice and

misunderstanding between the peoples of the earth; and if this is not the

purpose of documentary; I would like to know what is.

The purist, I know, will argue that a commercial

film which has for its motive profit never can be a documentary. It is, I

think, idle to deny that this motive is a force which dictate a policy and the

selection of subjects, and that it may limit the production of films which

attempt to achieve a purpose beyond entertainment: This may be so; but to argue

that because films are produced by this motive their integrity of purpose and

social significance are destroyed seems to me to be complete nonsense.

It is impossible to say which type of film is

more desirable: it's a matter of taste. But it would be regrettable if any one

type of film predominated. I think we want a well-balanced output; we' want our

escapist pictures and our realist pictures, but whether we shall get them

depends upon the public as well as producers, who can hardly be blamed for

studying box-office returns and gauging public taste accordingly; and whilst

the general demand is for films which attempt nothing more than to provide

entertainment, these are bound to predominate, but not, one hopes, to the

complete exclusion of the story-documentary.

This, I think, raises a serious issue of

principle. There can be no doubt that film is the most persuasive and forceful

medium for the dissemination of ideas, and as such its potential influence

either for good or evil is immeasurable. The acceptance and appreciation of

this fact imposes upon those who have the power to wield this influence the

gravest social responsibility. The manner in which they accept this

responsibility can only be determined by the production policy they formulate

and the balance of output between the realist film, whose purpose is to

dramatise an objective assessment of contemporary issues, and the entertainment

picture pure and simple.

If for the sake of argument, our civilisation

were in danger of being blotted out by an approaching ice age and the output

from British and American studios was concerned with nothing but Wicked Ladies,

Caravans, Carnivals, Magic Bows, Wonder Boys, Ziegfeld Follies, there can obviously

be little merit in the inner realism these films achieve, because the overall

policy of production is a deliberate retreat from a realistic point of view and

appreciation of the dangers and possibilities of approaching catastrophe. In

such a hypothetical situation cinema would have contributed nothing and

achieved nothing but to have become an opiate providing more and more

convincing means of escape from a world becoming more and more frightening.

An ice age does not threaten us, but an atomic age does.

PAT JACKSON

Penguin Film Review, 3, 1947

Courtesy: Andrew Pike.